By Abdul Brima for the China Dialogue

Malen Chiefdom sits on a dusty highway, 90 minutes’ drive from the district capital of Pujehun in southern Sierra Leone. The past decade has seen the landscape here transformed. Gone are the bushlands and subsistence farms more typical of this region. In their stead are thousands of hectares of oil palms.

Equally transformed is the peace and tranquillity of this far-flung corner of West Africa, rocked by violence and division since the arrival of the oil palms. The conflict over land that disaffected locals say was taken from them without their consent or proper compensation continues to this day. Meanwhile, the plantation company at the heart of it all has just been awarded the coveted seal of approval by the world’s leading sustainable palm oil body, the RSPO.

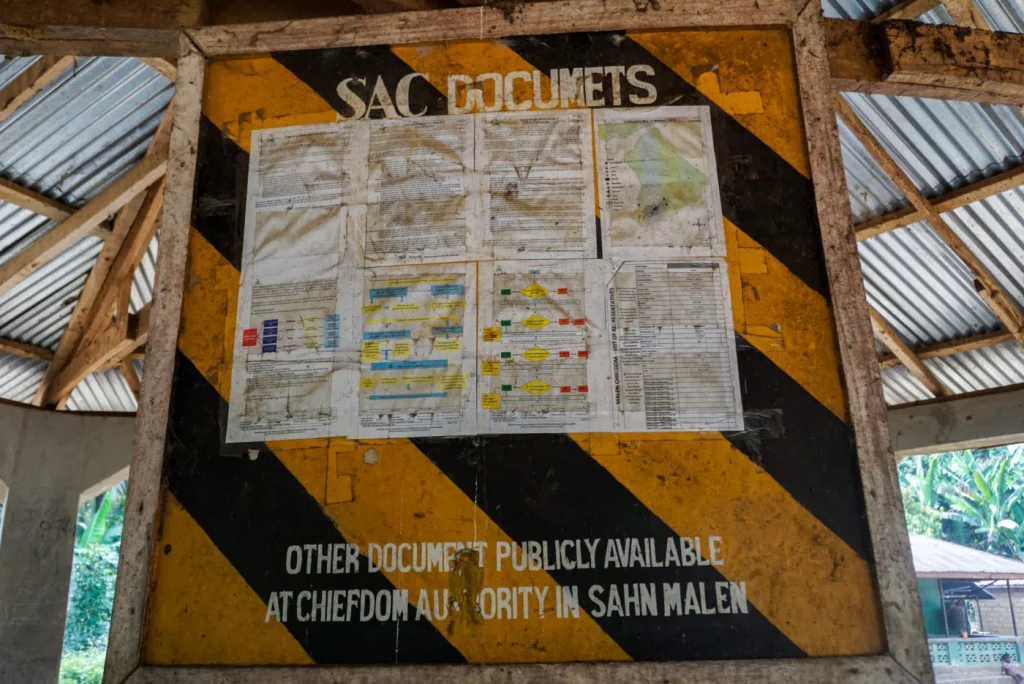

It all started in 2011, when the Socfin Agriculture Company (SAC) entered into a 50-year land lease agreement with the government of Sierra Leone and Malen’s local authority, the Chiefdom Council. SAC is a subsidiary of the Socfin Group, an agro-industrial multinational headquartered in Luxembourg. The original agreement leased 16,249 acres (6,576 hectares) to the company, but additional agreements over subsequent years have added substantially to that number. On paper, SAC’s concession currently covers 18,473 hectares (ha), nearly 70% of the chiefdom’s total area of 27,000 ha. Of this, 12,349 ha is now planted with oil palm, making it the largest active oil palm plantation in the country, according to data from non-profit GRAIN.

A decade of conflict

This land deal has proved controversial since the beginning. A selection of community members denounced it as illegitimate shortly after the signing of the first lease. Organised under the Malen Affected Land Owners Association (MALOA), in October 2011 they sent a letter to the government claiming among other things that the agreement was made without transparency or proper consultation with local stakeholders, and that compensation for the land leased was “a pittance” and “unacceptable”. The letter also accused Malen’s Paramount Chief Victor Kebbie – head of the Chiefdom Council and the main force behind the deal – of accepting bribes from SAC and intimidating landowners into signing the lease.

In the same month, tensions over the deal erupted into a protest, with over 100 landowners blockading roads leading into SAC’s concession area. This was met with the arrest of 40 people, 15 of whom were charged with “riotous conduct, conspiracy, and threatening language” according to US thinktank the Oakland Institute.

Since then, the situation has continued to escalate, leading in January 2019 to violence that resulted in the deaths of two men from gunshot wounds. In their report on the incident, local NGO Green Scenery, which has followed the conflict since the beginning, alleges human rights abuses, warning that the use of “arbitrary arrest” and “excessive force” by a “heavily armed military and police presence” in the chiefdom have resulted in “an unprecedented climate of tension and fear”.

There have been many attempts to resolve the conflict over the years, but none has so far succeeded, according to the Belgian arm of global human rights organisation FIAN. In 2018, Sierra Leone’s president, Julius Maada Bio, made a campaign promise to resolve the situation – a promise he followed through with once elected, by setting up a mediation committee. The committee proceeded to investigate, and the following year submitted a 17-page report supporting many of the grievances of the community against SAC and the Malen authorities. These included the fact that SAC’s concession exceeded its on-paper area of 18,473 ha by more than 650 ha. Although a leaked version of the report is freely available online, it has yet to be officially released. According to MALOA and NGOs supporting the group, no action has so far been taken by the government in response to it. The latest effort to mediate, as part of a two-year peacebuilding project funded by the UN Development Programme and the World Food Programme, has also fallen foul, with MALOA again expressing their dissatisfaction after apparently not being invited to participate.

Enter the RSPO

It was against this backdrop that, in December 2021, the plantation and its mill were awarded initial certification by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). This means that all of the palm oil produced by the plantation is now certified as sustainable: it is deemed to have met the RSPO’s Principles & Criteria – a wide-ranging set of standards that serve as a benchmark for measuring sustainability within the palm oil industry. Central to these standards is respect for community and human rights, including the need for “free, prior and informed consent” from users when their land is repurposed for oil palms, and proper compensation for the loss of user rights.

To gain RSPO certification, SAC went through a lengthy audit process – including two visits to the plantation by third-party auditor SCS Global Services in the second half of 2020. According to their report, which was only made available on the RSPO’s website in February this year, SCS Global’s team met with a wide range of stakeholders during their audit, including MALOA (although MALOA seem to deny this). The report recorded the grievances aired by each party during these meetings. And yet, in its findings, it only listed three “observations” against RSPO principles applicable to the land conflict. Observations are considered no more than “notes from the audit team”, and corrective actions are “voluntary and do not affect the standing of the certification”.

Learn more

To access SAC’s RSPO certificate and the audit report, visit: the RSPO’s website and search for “Socfin Agricultural Company”.

The audit report listed four “critical nonconformities”, which if not corrected would lead to a failure to gain certification. By the end of last year, when certification was granted, three of these had been corrected by SAC. The one that remained referred to the clearance of land without first assessing it for its conservation value or value as a carbon store. SAC was given 12 months to find a way to remediate or compensate for this or have its certificate suspended. The audit report states that the RSPO is confident the company is “committed” to this process. But the body has also rejected all of the remediation methods SAC has so far proposed. It seems there are “difficulties” finding a way to make amends in Sierra Leone, so SAC’s latest remediation proposal is a project in Cameroon instead.

Given how little time remains and how controversial a sticking point this appears to be, SAC may well lose its new-found sustainable status come the end of this year.

‘We were forced into it. We had no choice.’

The Malen land deal and the arrival of SAC have had a very real impact on the ground, quite beyond the violence of the conflict.

Before being covered by oil palms, the land now under SAC’s control was the main source of food for the people of Malen. A 2019 report by FIAN describes how communities farmed “a nutritious range of foods”, and even land they’d left fallow to regain its fertility – a practice of rotational agriculture common across Sierra Leone – “continued as a source of firewood, bush meat, wild plants, honey and herbs”. The loss of access to this land has had a major impact on food security in the chiefdom, the report says.

Even those who were compensated for the loss of their land are suffering this impact. Hawa Koroma is a widow in her early 60s who lives in the village of Heinie, where she raised her eight children. She received a one-off payment of two million leones (then worth roughly US$460) when she leased her land to SAC in 2012. This money was quickly used up paying for school fees and buying zinc to fix her leaking roof. She continues to receive a small sum of 20,000 leones (currently about US$1.50) as rent every year – but this in no way makes up for the loss of her land, on which she used to be able to grow enough crops to feed her family. Now, to survive, she relies mainly on backyard gardening and a small business selling cooking oil, cigarettes, biscuits and other food items from a wooden table on her veranda.

Along with her land, Koroma lost an asset that many in rural Sierra Leone consider vital: her own oil palms. The species is native to West Africa – those households with enough land will tend to cultivate the crop, producing oil from the fruit using traditional, manual techniques. The oil has long played a central role in cuisine and culture across the region, and remains valuable not only for food security, but also to the grassroots economy. Koroma used to be able to sell her surplus palm oil, but can now no longer rely on this much-needed boon to her household finances.

For Koroma, though, there are deeper injustices. She claims her household owned four acres (1.6 ha) of land, but SAC only compensated her for two acres after making their own measurements. Plots of land have yet to be clearly mapped in rural Sierra Leone, with traditional property boundaries “demarcated by things like big branches”, says an article by Mongabay. Even with the best will in the world, this makes things difficult when a company like SAC moves in with a survey team. For MALOA, it allowed for “high levels of corruption”, with SAC cheating landowners “by entering the wrong figures”.

Even with fair demarcations, Koroma is adamant she would not have leased her land if she’d been free to choose. “It was a matter of either leasing the land or running the risk of losing both the land and the money. We were forced into it. We had no choice,” she says.

One of the reasons Koroma felt she had no choice takes us back to Malen’s Chiefdom Council and Paramount Chief Victor Kebbie. Paramount chiefs wield a huge amount of power in rural Sierra Leone. This is in large part due to the laws governing land tenure. Since colonial times, when “native ownership of the land by the tribes” was recognised, a system of either community or family tenure has been in place in rural areas, according to an analysis of the Malen deal by legal adviser Patrick N. Johnbull. However, due to the communal nature of this ownership, land is seen to be held in trust on behalf of these groups by the “Tribal Authorities”. These continue to be defined in Sierra Leone’s current land laws as: “paramount chiefs and their councillors, and men of note, or sub-chiefs and their councillors, and men of note”.

What this means in practice differs from chiefdom to chiefdom. In Malen, the paramount chief is “the highest custodian” of land with a central role in granting access to it, according to a case study by Welthungerhilfe, a German NGO active in the region. Add to this the fact that Victor Kebbie is, according to Mongabay, one of the most powerful paramount chiefs in the country, and it’s easy to understand why a landowner like Koroma might feel obliged to do as she’s told.

The other side of the coin

Why then did Malen’s paramount chief feel inclined to turn over 70% of his chiefdom to an oil palm plantation? Chiefdom Speaker Shempbe Robert Moiguah gives an answer of sorts: development. “Before this time, there were lots of thatched houses in Malen. But now there are very few, and the population has grown, so too the [number of] good roads,” he says, half asleep under the eaves of his home. Moiguah insists that SAC is in the area to stay, and that the Chiefdom Council will do what is necessary to make sure the company fulfils all its promises to the community.

Many of these promises were laid out as “community development action plans” in the company’s 2011 Environmental, Social and Health Impact Assessment, a necessary prerequisite for obtaining an environmental licence to operate in Sierra Leone. In its 2019 report, FIAN analysed the company’s spending against these plans between 2011 and 2017, and identified “major gaps” between what was promised and the reality on the ground.

One such gap is a planned smallholder out-grower scheme, whereby local farmers could sell the oil palm fruit they produce to the company. SAC earmarked US$7,824,000 for this scheme between 2014 and 2025. FIAN found that none of this had been spent by 2017.

Other promises have yielded results, though. More has been spent on building and maintaining roads around the plantation than had been planned. While this clearly benefits SAC, it does also make it easier for local residents to get around. Investment in community projects such as wells and schools are also clearly in evidence.

It is also true that many have benefitted from the employment the plantation has brought to Malen. “Working in this company is good for me,” says Ibrahim Amara, a SAC employee. “If it was not for this job, I would struggle to provide for my family.” Amara works as a palm fruit harvester who also cleans around the plantation. With the money he earns, he has managed to build himself a house, and can also send his children to school. Despite allegations of poor working conditions by groups like MALOA, there is still a long queue of people waiting to be employed by the company.

Amara’s hands show how hard the work on the plantation is (Image: Saidu Bah / China Dialogue)

SAC’s presence has also had a trickle-down effect, creating jobs within the community. Mohamed Keita is a tailor who runs a shop in Malen’s main town of Sahn, and was contracted in 2015 to make uniforms for the company’s workers. “I make roughly 500 uniforms [a year] and earn about 10 million leones (currently just over US$750) from that, all thanks to the company,” he says.

‘Now they are polluting our water’

The pros and cons of the land deal have been forensically examined by both NGOs and the media. Less well covered is the environmental impact SAC’s arrival has had in Malen.

Beyond the loss of their farms and the bushland that once provided for them, local people are also being impacted by pollution. The culprit is not only the roughly 100 metric tonnes of chemicals used on the palms each year to keep them productive, but also the mill, built on the plantation in 2015 and expected to produce over 45,000 tonnes of crude palm oil this year, according to the RSPO’s audit report.

Those living within the plantation concession area (an extraordinary total of more than 32,000 people by FIAN’s reckoning) are especially vulnerable due to the lack of buffer zones, according to the 2019 government report on the land conflict. Both the company’s Environmental, Social and Health Impact Assessment and the RSPO’s Principles & Criteria emphasise the need for buffer zones or greenbelts around plantations. This is not only to keep communities safe from pollutants like agrochemicals, but also to protect watersheds and conserve biodiversity and ecosystem functions.

Fisher Salia Lebbie, 53, has lived all his life in the tiny village of Massao, 1.5km downstream from SAC’s mill on the banks of the Malen River. Lebbie’s community relies on the river for their drinking water, as well for transportation and washing, and as a source of food.

“I grew up knowing this water as the source of our livelihood. I learnt how to fish and ride boats in it,” says Lebbie. Now without as much land as before to grow groundnuts, cassava, beans and other crops, the river has become even more essential. “My family’s survival depends on it,” he explains.

But all is not well with the river. Lebbie describes how “there are times the water changes colour to brown and sometimes we see dead fish floating in it”. He’s clear of the cause, accusing SAC of releasing waste from the mill, indirectly via the occasional overflow of ponds used to treat the effluent, as well as directly through pipes that empty straight into the river and its wetlands. “They took our land, and now they are polluting our water,” he says.

The situation is equally troubling in Kortumahun, which is right next to the mill. Residents say the stench generated by waste from the mill is so bad they must cover their noses. They are also worried about the potential health implications, complaining of not being able to sit outside at night because of the profusion of mosquitos – a situation they blame on the ponds used to treat the mill waste.

For 34-year-old farmer Sidie Swaray, the situation really hit home when his two children came down with malaria in December last year. The problem gets worse during the rainy season (May to October), he says, when people also report more cases of diarrhoea and cholera.

Roughly 30 minutes’ drive south from Kortumahun is Hongai village, where there is a small community health post managed by two healthcare providers. Josephine Yankuba, the nurse in charge of the facility, says they provide care to nearly 2,000 people across 10 catchment communities including Kortumahun and Massao.

Yankuba confirms that cases of malaria, cholera and diarrhoea are common during the rainy season, but says they now see high numbers even during the dry season (November to April). Between September and December last year, the facility treated 69 cases of diarrhoea alone – many of the patients were children. Yankuba attributes the situation to a lack of access to clean water, with many patients complaining their rivers have been contaminated by SAC’s operations.

“We have cried a lot about this pollution. We have even lodged a formal complaint to the Environment Protection Agency,” says MALOA Coordinator Kinney James Blango. He tells China Dialogue the government agency has investigated the matter, but the affected communities still await its findings.

Palm oil for all?

One of the reasons SAC gives for its presence in Sierra Leone is the unmet domestic demand for palm oil. On its website it claims that the average monthly consumption in the country is one kilo per person. Traditional, artisanal production is unable to meet this demand, it says, and in 2019, “50% of oil consumed on the local market was imported”.

SAC gives the strong impression that this consumption is all food-related, but this is misleading. A 2019 value chain analysis by the European Commission agrees that there is an “overall deficit of palm oil for food use” in Sierra Leone. But it argues this is mainly because high volumes of the oil are diverted into the production of soap for export to the wider West African market. As such, it would seem SAC’s self-proclaimed goal to be “the main palm oil supplier on the domestic market” has very little to do with supporting food security in Sierra Leone, which the company acknowledges is “at the bottom of the list of food-producing countries”.

On the ground, the deficit of what in Sierra Leone is considered an essential food item is clearly evident in its high prices – a pint of palm oil currently costs up to 6,000 leones (US$0.45). This, combined with one of the world’s highest rates of inflation (that pint of palm oil has more than tripled in price over the past decade), has made palm oil unaffordable for some consumers, especially in a country where more than 50% of the population lives on less than US$1.25 a day.

It is only those who have access to their own oil palms that enjoy some protection from these market pressures. In Malen, this means the small group of landowners who have resisted the expansion of SAC’s plantation.

Bockarie Landa lives with his wife and five children in Jao, a village to the northeast of SAC’s plantation still surrounded by forest. Landa owns about three hectares of land, which includes his own small plantation of oil palms. He has never regretted the decision to keep hold of these assets, but it wasn’t easy. He wouldn’t have been able to resist pressure from the Chiefdom Council without the support of MALOA, many members of which have suffered repeated arrests and threats to their safety. And now Landa and those like him in his community are fighting again – this time for the freedom to work their own farms.

“They don’t allow us to process our palm oil. They try to stop us because they know that if we process our oil, we will get enough money and we will not need to work for them,” he says.

Bockarie has to keep the palm oil he makes secret, producing it in a hidden location in the bush, and smuggling the oil to market in a canoe. “Otherwise, they will seize all of it and arrest me for stealing [oil palm fruit] from the company,” he says. Others in Bockarie’s village repeat the same allegation, noting that some community members have previously been arrested and forced to pay a hefty fine or risk being thrown into prison.

What of the future?

SAC’s recent success in gaining RSPO certification gives its plantation in Malen an extra air of permanence. The palms are already mature, and the company has made good on its plan to provide thousands of jobs for Sierra Leoneans – although half of the 3,027 total SAC advertises are not permanent employees but rather “daily workers” and contractors. In short though, it’s not going anywhere. Even the government’s 2019 report, which was highly critical in its findings, accepts that as a given. It says all the parties agree “the company should continue with its operations, in an atmosphere of inclusiveness, mutual respect, trust and benefit.”

SAC and its 18,473 ha stand in stark contrast to other attempts to develop oil palm plantations in West and Central Africa since the early 2000s, when foreign companies rushed to acquire land on this “new frontier”. As a new report by Chain Reaction Research shows, things have not gone according to plan, “with substantial disparities between awarded concessions and areas eventually developed into industrial oil palm plantations”. One of the reasons given for these failed plans is widespread community resistance.

Why then has the unflagging opposition to SAC by groups like MALOA failed to stop its expansion? One reason is government involvement in the land deal. It was the government that invited the Socfin Group to Sierra Leone, and the government that signed head leases with Malen’s Chiefdom Council – SAC only entered into sub-leases, not directly with the authorities in Malen, but with the government.

This is perhaps why SAC has been able to remain relatively aloof to the whirlwind of accusations and protests around them. They are not above attempting to set the record straight though, nor to legal action against groups like Green Scenery, which they accuse of defamation. It is also, perhaps, why the government has largely ignored complaints about pollution and inadequate compensation, according to MALOA’s Blango.

Blango says his group of landowners want their land back. Failing that, they want the company to sit with them and renegotiate the terms of the deal. “We are not against the company. All we want is fair and honest dealing. We cannot be landowners and be suffering like this while the company is making millions of dollars,” he says.

This article is part of our ongoing series on palm oil.

Abdul Brima is the West Africa Regional Editor for China Dialogue, currently based in Freetown, Sierra Leone. He has worked as a broadcaster, editor, journalism trainer/mentor, multimedia producer and freelance writer over 10 years.