By Kemo Cham

In the face of vaccine apathy, fuelled by false information spread online, the best response is a counter narrative that spreads hope, researcher Dr Heidi Larson says.

Dr Larson, the mastermind of an initiative that seeks better understanding of vaccine skepticism around the world, advices journalists to avoid reacting directly to fake news about vaccines and other issues or risk amplifying the wrong messages.

“What the world needs now more than anything else is hope, and we need to generate that hope,” she told a group of science journalists and other communicators during a global media dialogue on effective communication on vaccine science.

Larson, the author of “Stuck: How Vaccine Rumors Start – and Why They Don’t Go Away”, is the founding head of the Global Listening Project, which investigates public trust, coordination and other dimensions of societal preparedness/Social Cohesion, emotions, and equity.

Vaccine hesitancy is an age-old reality, but COVID-19 fuelled the largest backslide in recent decades. With her work, Larson seeks to uncover why this is so even with the existence of “compelling evidence” that vaccines work.

The Global Media Dialogue, titled: ‘When facts are not enough,’ was meant to share insights with journalists about how to communicate vaccine science in a way that shows why it matters, with the goal of helping people make better decisions about their health and inform appropriate policy decisions.

The programme, hosted by the Internews Health Journalism Network and streamed live on October 12, entailed a 19-minute discussion by Larson, followed by inputs by three discussants, two science journalists and an activist.

Larson’s presentation focused on the findings from one of her latest work on vaccine confidence, which shed light on the factors that drive apathy towards the life-saving commodity in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Larson founded the vaccine project 13 years ago in 2010, after working with Unicef and around the launch of the global Vaccine Alliance – Gavi – which coincided with the introduction of the Polio vaccine. She recalls observing how governments and people questioned vaccine, leading to an “increasingly” growing trend globally and loss in confidence in vaccines.

“It was in small ways but in more and more places in the world,” she said, explaining that it caused her to leave the UN children’s agency and forming the vaccine confidence project “to start to listen and measure and draw a map.”

Larson said measurement was important for her because people were asking how big of a problem it was or whether it had gotten worse.

“And you don’t know if you don’t have a benchmark and you don’t have a baseline to measure it against,” she said.

In 2015, Larson and her team launched the Vaccine Confidence Index, through which she has been collecting data in over 150 countries.

Fast forward in 2021, the project was expanded to look at public confidence in a wider range of issues, but in the context of COVID-19, as the world entered the post-pandemic recovery phase.

The Confidence Project was designed to look at people’s feelings and thoughts generally, but also their perceptions about vaccines. That resulted into the GLP.

Funded by the MacArthur Foundation, GSK, Moderna and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the GLP seeks to dig beyond issues around vaccines. It maps and interprets public sentiments in 71 countries in order to find ways to prepare people for pandemics and build social cohesion.

Part of the latest study conducted as part of this initiative – the COVID-19 Global Confidence Measure – futured in Unicef’s World Children’s Report 2023. Over 70, 000 respondents were involved, and 14, 500 of them in Africa.

The unreleased data shared by Larson during the dialogue session shows that 53 out of 55 countries surveyed had a drop in confidence around the basic importance of child vaccines.

“That is pretty significant. We see ups and downs with perceptions of safety and effectiveness, but it’s very real. In fact, we have never seen a drop in perceived importance of vaccine,” she said.

The decline later went down to 44 percent in some countries, the data shows.

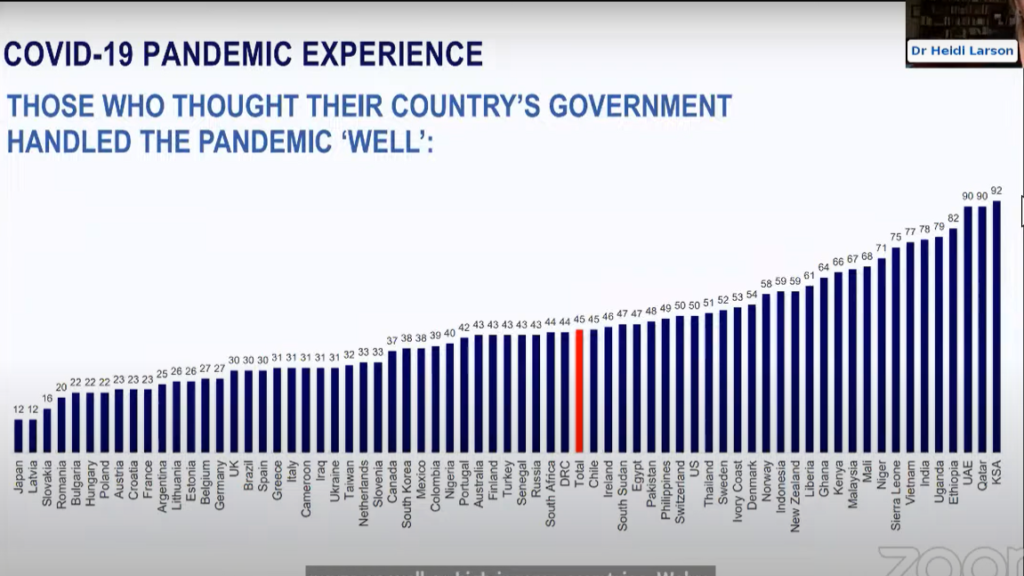

A random selection from the findings further show that an average of 45 percent thought their countries handled the COVID-19 response well. Larson considers that as the “biggest” predictor of the unwillingness of people to take vaccines.

The study also looked at mental health related issues and food security, among others.

The discussion it generated highlights the similarities of the issues captured in the report and the reality on the ground.

The researcher said addressing all the issues depend largely in the hands of the media.

A component of the survey question assessed the level of trust in various sources of information. Social media emerged the least trusted source.

South African youth activist and member of the Vaccine Confidence Project team asked how could those who seek to spread facts counter the more dedicated false information spreaders in getting the public’s attention.

Larson’s response stresses on the message of hope: “We need to talk about hope, we need to build hope.”

According to the researcher, the public health community contributed to the information chaos on social media by refraining from using the space, thereby leaving it “widely open” for bad forces to take it over.

The consequence is illustrated in the report, in how citizens in perceive their government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In Africa, for instance, 69 percent felt that the pandemic was exaggerated.

Globally, on average 54 percent of people had doubts or reservation at the time they got vaccinated; 72 percent felt relieved about being vaccinated, while 26 percent regretted having been vaccinated.

In Cameroun, 63 percent of the people regretted having been vaccinated, the highest negative feeling after getting the shot, while conversely, in Vietnam, 98 percent were relieved.

With 62 percent, Africa, alongside parts of Asia with 54 percent, had the highest amount of doubts for taking the vaccine. But the African continent, with 86 percent, also had the highest relief after the shot, while south Asia with 37 percent, had the highest regret.

Larson says this shows how public sentiment shifts over time.

“One of the things this tells us is how volatile emotions are and importance of paying attention to them,” she said.

The testimonies of the respondents, according to Larson, also revealed that vaccine acceptance does not equal vaccine confidence. Many people, she said, took the vaccine for various reasons, not necessarily for believing in its efficacy. Some simply wanted to go to the restaurant or the pub or the football match or to travel, and the only way they could do that is taking the vaccine, she said.

Some people who even knew that vaccines work, refused to take it for one reason or the other.

“Confidence can be a predictor of vaccine confidence. If they are confident, they are more likely to take the vaccine. But it is not just about confidence, when a mandate is involved,” she stated.