By Brima Sannoh

Tucked away in the southernmost reaches of Sierra Leone lies Pujehun District, a region once celebrated for its thriving agricultural output and natural abundance. Fertile soil, reliable rainfall, and industrious farming communities once made Pujehun a symbol of rural self-sufficiency and prosperity. But that chapter now lies buried beneath layers of hardship, conflict, and neglect.The decade-long civil war ravaged Pujehun, destroying its infrastructure, displacing its people, and disrupting farming systems that had fed both local and neighbouring populations. Fields went untended, livestock were lost, and the expertise of entire generations of farmers was either uprooted or forgotten. The war did not merely pause development; it reversed it.

In the post-war years, Pujehun has struggled to find its footing. While the scars of conflict remain visible, new efforts are being made to revitalise agriculture and combat chronic food insecurity. One such initiative is the Feed Salone Programme, launched in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This national scheme seeks to address hunger and boost self-sufficiency through food aid, training, and investment in rural infrastructure. Pujehun is among the districts targeted for support.

However, recovery has proven to be a long and difficult journey. Transport remains a major barrier. Poor road conditions make it nearly impossible for farmers in remote communities to access urban markets or receive necessary farming inputs. Inadequate storage facilities and post-harvest management systems have resulted in substantial crop losses due to spoilage and pests. And despite government commitments, many rural farmers still lack access to essential tools, irrigation systems, and mechanised equipment. Local farmer Joseph Bockarie, who relies entirely on subsistence agriculture, shared his frustrations:

“We struggle to get seeds, fertilisers, and technical support. The government says it supports agriculture, but that help rarely reaches us here in the villages,” he said.

“Farmers are the backbone of this country. Without us, there’s no food, no exports, no economy.” Messie Kanneh, a widow and mother of seven, echoed that sentiment. “I registered with the government as someone in need, hoping for seeds, tools, and training. I received nothing. Then the floods came and destroyed everything we had grown. We lost everything.”

Many civil society voices argue that this is not how it used to be. According to Ibrahim Borgiwa Swaray, head of the Pujehun District Civil Society Forum, Sierra Leone was once a net exporter of staples such as rice, cassava, and groundnuts.

“The country’s climate and soils once made us an agricultural powerhouse in West Africa,” he said.

“Today, we import over $100 million worth of rice annually, one of the highest figures in the region. Conflict and mismanagement have gutted our agricultural sector. Many farmers still haven’t returned to their land. Infrastructure is gone. Soil fertility has declined. The effects are devastating.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) report supports this account. It documents the extensive damage inflicted on agriculture during the war, particularly through displacement, destruction of irrigation networks, and the disruption of food supply chains. But the report also points a finger at post-war governance, citing corruption and poor management as ongoing barriers to recovery.

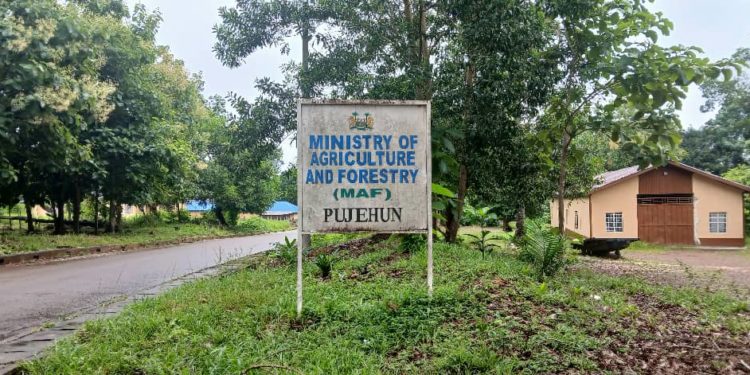

Nevertheless, there are glimmers of progress. According to Lucky Koker, District Agricultural Officer for Pujehun, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry has in recent years introduced several reforms to reposition agriculture as a driver of economic recovery.

These include:

- The Agriculture for Transformation Agenda, which focuses on commercial farming, productivity enhancement, and market modernisation;

- The National Food Security Strategy, which promotes access to credit, modern tools, and training for rural farmers;

- The establishment of Chiefdom Youth Farms and the annual celebration of World Food Day to promote agricultural awareness.

“We’ve trained more extension officers than ever before,” said Koker.

“Farmers are learning modern techniques that can transform their yields. The goal is clear: we must achieve food self-sufficiency.”

Still, the gap between ambition and reality remains stark. Until national policy translates to visible, lasting support in places like Pujehun, the district’s journey from prominence to obscurity, and hopefully back, remains unfinished.

This report was produced with support from the Africa Transitional Justice Legacy Fund (ATJLF), through the Media Reform Coordinating Group (MRCG), under the project:

‘Engaging the Media and Communities to Change the Narrative on Transitional Justice Issues in Sierra Leone.’