By Kemo Cham

The Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) on Thursday praised progress in Sierra Leone’s response to the Mpox epidemic and called for the deployment of more resources to sustain efforts towards breaking the chain of transmission.

Data from the continental public health agency revealed continued decline in cases of the viral disease in country, which a top official say calls for increased efforts to maintain the trend. Dr Ngashi Ngongo, Head of the Africa CDC’s Incident Management Support Team (IMST), attributed the reduction in cases to the intensification of community engagement, which he said must be reinforced.

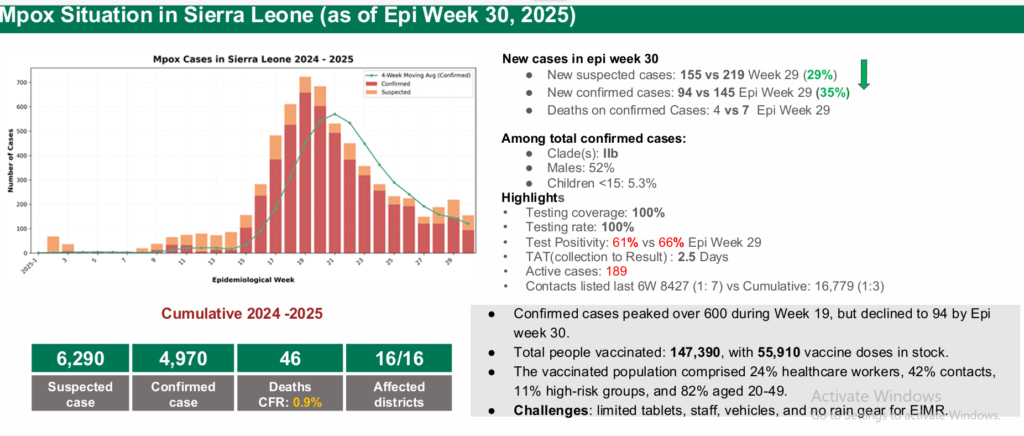

An analysis of data from early May (Week 19), the peak period of the epidemic in Sierra Leone, to August 3rd (Week 30), revealed that cases had dropped from 600 per week to about 94 per week, according to Africa CDC.

“What that shows is that surveillance is improving,” Dr Ngongo told reporters at the agency’s weekly virtual press briefing. He added that it also meant that the country was moving from passive surveillance to active surveillance.

Sierra Leone registered its first case of the epidemic in January 2025, prompting the declaration of a public health emergency by the government. Within three months, the country experienced a surge in cases. By early May, it had taken the lead in the Mpox outbreak in Africa, when it accounted for roughly half of all confirmed cases on the continent, according to Africa CDC data. Since then, Sierra Leone has been ranked among four countries leading the trend of infections, alongside the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda and Burundi.

Daily updates from the National Public Health Agency (NPHA) show that as at Thursday, August 7, Sierra Leone had recorded a cumulative confirmed cases of 5,096, with 46 fatalities.

In the early days of its response, Sierra Leone mounted the Operation Find Them All, a community surveillance programme that saw health workers moved into communities to identify suspected cases and contacts of infected persons, amid sensitization on the virus. That process was however relaxed, amid reports of resource constraints.

Dr Ngongo believes that the reactivation of the community surveillance activity, along with the deployment of additional 200 community health workers in the last two months, led to the current decline in cases being witnessed. He however stressed that these efforts are needed be sustained to continue the downward trend.

“They need resources to get supplies on IPC (Infection Prevention Control). They need resources for case management. They need resources to pay and support community health workers,” Dr Ngongo, who is also the Chief Adviser to the Africa CDC Director General, said.

The Africa CDC data shows that even at the continental level cases are dropping. And according to Dr Ngongo, this points to a need for acceleration of efforts, particularly with regards surveillance.

Mpox, previously known as monkeypox, is a virus that causes fevers, headaches, and painful boils on the skin. It can spread from infected animals to humans, and from person to person through close physical contact, including sexual intercourse.

The current epidemic started in 2023. Since the beginning of 2024, Africa has registered a total of 174, 597 suspected cases and 48, 797 confirmed cases, according to Africa CDC data, which shows decrease in both number of suspected and confirmed cases.

Dr Ngongo said Sierra Leone is one of the best stories in terms of declining cases of Mpox during the period under review. But concerns remain as its neighbours – Liberia and Guinea – are experiencing upward trend in cases, with both countries said to be dealing with Clad IIa and IIb co-circulations in their populations. In Guinea, the outbreak remains isolated to three regions – the capital, Conakry, Faranah and Kindia – with 396 confirmed cases as at August 3rd. Liberia has had 416 confirmed cases as at the same period.

Dr Ngongo said while Guinea had done well with community surveillance at the beginning of its outbreak, limited resources, weak surveillance systems, delayed case detection, and low community awareness are now affecting timely outbreak response.