By Stephen V. Lansana

George Kamara [Not his real name] works in “Dama pit”, an underground gold mining site in Salowa Village, Penguia Chiefdom in Kailahun. The 17-year-old is part of a group that draws the gravel from the pit.

George relies on this part-time job to pay for his education. He is a Junior Secondary School Level One (JSS I), and he attends the Grace Academy Secondary School in the southern region, Bo City, from where he traveled over 300 miles to spend his second term [Easter] holiday with family.

The boy has to get up from bed every day at 6am to be at the mining site at 8am. He does this usually twice a week, working 11 hours each day. He is not paid with cash; rather, the site manager gives him a portion of the “gravel”.

“I sometimes get NLe 50 or NLe 60 after washing the gravel each day,” he said. “On a lucky day, I may even get over NLe 400.”

Sometimes George doesn’t get any gold. But he is okay with that. His major challenge, he said, is the difficulty getting pain medicines, which he needs after every day of work, because of the hard nature of the job.

Under Sierra Leonean law, what George is doing is called child labour, which is prohibited.

Child labour deprives children of their childhood, potentially endangering their health and stripping them of their dignity. It is harmful to their physical and mental development.

Sierra Leone is a party to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child which calls on State Parties to protect the right of the child from economic exploitation and from performing any work that is likely to be hazardous or to interfere with the child’s education.

In Sierra Leone, all jobs that pose danger to the health, safety or morale of a child are prohibited, like going to sea, mining and quarrying, and porterage. The country’s minimum age for light work is 13 years.

Regardless of this, child labour remains rampant in the country.

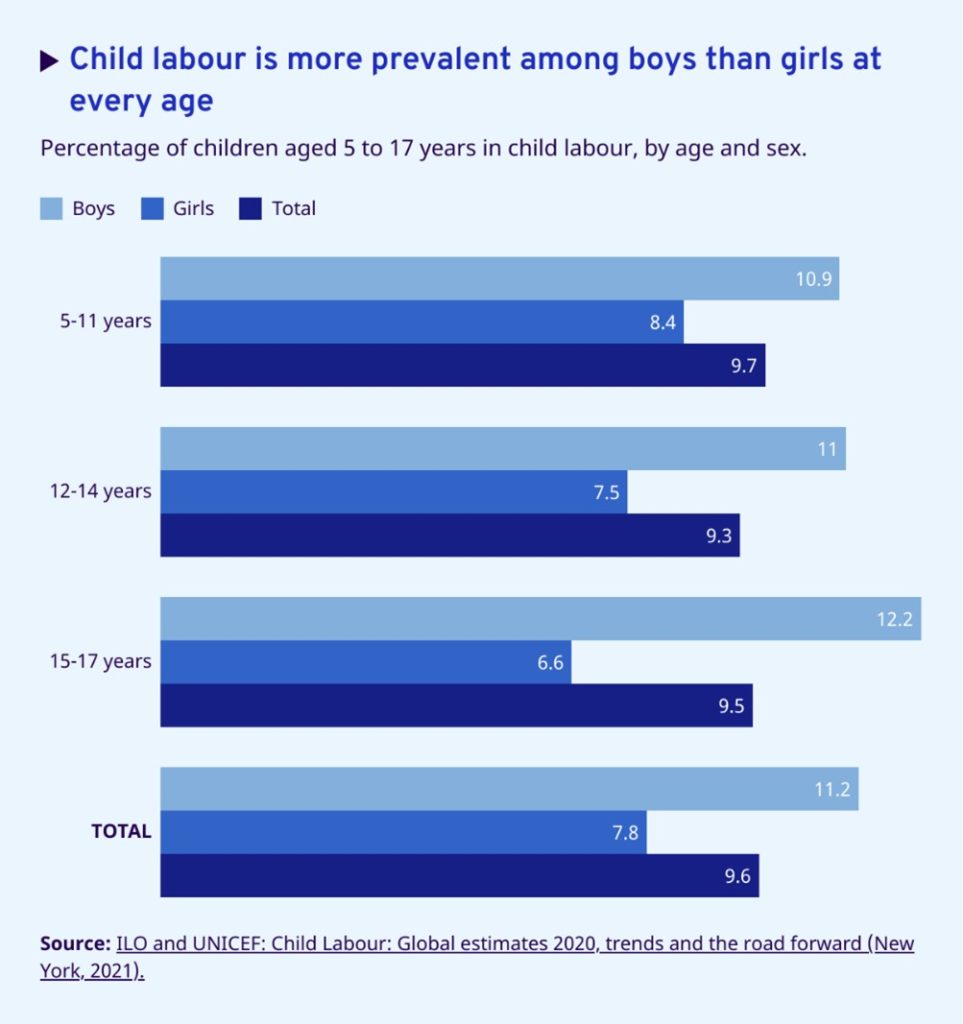

Child labour remains an important concern across the spectrum of children aged 5 to 17. Of the 160 million children in child labour, globally, 89.3 million are young children aged 5 to 11; 35.6 million are children aged 12 to 14, and 35 million are children aged 15 to 17. The 160 million children involved in child labour account for almost 1 in 10 of all children worldwide.

According to a study conducted in Sierra Leone by the African Programming & Research Initiative to End Slavery (APRIES) and partners in 2019-2020, the overall rate of child labor, based on direct prevalence estimates, was 36.2% in the Eastern Province among the household sample of children aged 5 – 17 years old.

The highest rates of child labor were found in Kono (52.3%), followed by Kailahun (34.7%), and Kenema (28.8%).

Over one-third of children in child labour are out of school, according to the joint ILO/UNICEF report, which states that children aged 5 to 17 years in child labour are not attending school.

Dr. Reuben Lewis, a Lecturer at Fourah Bay College (FBC), University of Sierra Leone, doubling as an expert in Trafficking in Persons, said that in most rural settings, children are not encouraged to go to school because of a lack of basic social amenities and the long distance to school. Therefore, he said, children will choose to go to the farm to help their parents.

Pa Sandy Taimeh, Chairman of the Child Welfare Committee (CWC) in Kailahun, said Child Labour in the district is especially prevalent in the mining areas of Penguia.

“In Penguia, they are doing gold mining and they sometimes use children. The Diamond miners in Daru were using children, but we [CWC] engaged them and they have stopped it,” he said.

Unlike in the mining sector, Mr. Taimeh believes that boys within the same age bracket of 16 and 17 involved in farming aren’t in child labour since they are paid with money they use to fund their education.

Nonetheless, Mr. Taimeh acknowledges the negative impact of child labour on the education of victims.

Brima Kanneh, a Teacher of Roman Catholic Primary School in Jojoima, Kailahun District, said that teachers sometimes select a few children on cleaning day to work in their farms or gardens.

Kanneh said that children who are involved in child labour have low performance in class as compared to children who are not involved in child labour.

He said that some class six children usually abandon school after taking the National Primary School Exams (NPSE) and form groups or clubs where they will go and work in farms for payment.

According to ILO, child labour is more prevalent among boys than girls at every age.

TRAPPED BY CHILD LABOUR

Kemoh Karim, aged 33, dropped out of school in 2002 when he was in Junior Secondary School Two (JSSII), following the death of his guardian [uncle]. He attended the Methodist Secondary School in Kenema. Consequently, he failed to achieve his childhood dream of studying medicine.

Karim was 12 years when his uncle died. He soon joined a Power Saw group, whose job is to transport timber logs from the bush to the roadside, so that they can be easily transported to town. He is currently involved in Gold Mining. Although he still nurses the idea of going back to school, he can’t imagine abandoning his source of income.

“I was not able to return to school again because I was trapped by the monies I was paid out of my labour,” he said. “Even now, enrolling in a skills training center is challenging because my source of income will cease. Besides, I do make more than most teachers in my community.”

Karim has been on this for 13 years now. He is now married with three children.

EFFECT OF THE BY-LAW

The community leaders in Penguia chiefdom including the Natural Mineral Authority (NMA) and the local chiefs have taken some action against child labour. For example, they instituted a by-law that prohibits it. Violators risk being fined NLe 500.

Abdul Dugba, a former Councilor of Ward 029 in Sandaru, Penguia Chiefdom, said child labour is a legacy of Sierra Leone’s civil war. He said the practice has persisted because children were getting more money than their teachers, therefore seeing no need to go to school.

“Those who take children to mining sites are trying to spoil their future. That is why we cannot allow such in our chiefdom,” he said, justifying the institution of the by-law.

“Mining can destroy the land, but if a child acquires education, it will benefit his/her families, the chiefdom, and the nation as a whole.”

Agnes Marrah, a parent of four children, said, “I don’t allow my children to work in the mining site because there is a by-law that prohibits us. If we allow children at the mines, the NMA, and the local chiefs will fine us NLe 500.”

WALKING AT A CONSTRUCTION SITE

Joseph Vandi [Not his real name], is among 15 other children who carry mixed concrete for the “floating” of a Market Building in Kailahun town. Joseph, 12, is a class six pupil of the Ahmadiyya Primary School in Kailahun town. He was preparing to take his National Primary School Examinations (NPSE), which will determine whether he proceeds to Junior Secondary School (JSS).

Joseph’s mother is a trader and his father is in the military. His father lives outside Kailahun town because of work. Joseph, therefore, tries to fill the gap the absence of his father creates in the family. He works to raise money to assist in the family’s financial needs.

A day earlier, a friend of his informed him about the opportunity, he said.

“I arrived at the site very early in the morning and registered for the work.”

Joseph had been working for three days at the site, for 12 hours each day, when I met him. He said he and his colleagues were paid NLe 50.00 (Equivalent to $2.22] on the first day. But they were interrupted on the second day when the Chief Administrator of the Kailahun District Council visited the site and ordered that they be relieved.

“So, I was paid only Le 20 [Less than $1],” he recalled. “I do not know why the council stopped us. I still came today, [Friday, April 16, 2023] which is the last day of the concreting. I am searching for money, which I give to my mother to help pay for my education. Even though my father usually sends money for her, it’s not enough for our welfare.”

Lahai Sheriff supervises construction work on the market. He hesitantly admitted to hiring a blend of adults and children to mix about 300 bags of cement on the first day. He said the children worked for about 12 hours, whilst on the second day the Chief Administrator told them to stop working. He said they stopped but that they returned to work on the third day.

Sheriff lamented that labourers are hard to get in Kailahun, hence their inclination to use children. He stressed that they are paid accordingly, in front of their parents.

The Chief Administrator, Jonathan Combey, lamented the effect of child labour, which is said to be fueled by poverty. And although he acknowledged its existence in the district, he said it was only prevalent in the business sector.

“In Kailahun, the most prominent form of child labour, which I cannot call child labour, is trading, because most children are selling for their parents,” he said, adding that he couldn’t ascertain reports of child labour in the mining sector in Penguia.

Mr. Combey said that the only way to address child labour is to first eradicate poverty.

“As a country, the government, through the National Commission for Social Action (NaCSA) gave money to vulnerable traders and parents, and most parents do start up a small business that will enable them to take care of their family, thereby preventing their children from child labour,” he said.

Combey said his Council cannot do more than the government is doing in providing alternative livelihoods to discourage child labour.

But Dr. Lewis, the trafficking in person expert, said children are normally exploited by people they know. He cited the practice of people going to the rural communities and taking children with promises of sending them to school, only to change the plan on arrival in Freetown or other urban centers.

Lewis said it has become culturally acceptable that when parents give birth to their kids, the kids will in turn help them even at a very tender age. This, he added, has left kids from poorer backgrounds highly exploitable.

“The government has not been able to deal with child labour. The Ministry has not been able to provide a more structured approach in handling “Men Pekin,” he said, referring to the term used to describe children under guardianship.

“They should have registered the children and ensure that they visit the homes of families who are raising foster children,” he added.

Lewis added that the government has been slow in the protection of children, particularly in the handling of the “Men Pekin” business. He suggested the use of digital technologies to keep track of children’s well-being.

“We have the Ministry of Social Welfare and the Ministry of Gender and Children’s Affairs. The Ministry of Gender has the mandate to look at child protection issues, whilst the Ministry of Social Welfare has the mandate of seeking the welfare of children. In this aspect, there is an overlapping of roles. In these circumstances, it is sometimes difficult to reconcile policy differences, which makes it difficult to address the issue,” he said.

Lewis said while the government established the CWC in every chiefdom, they are dormant because they are loosely established with little or no training and no financial support.

“Because of this, the CWC has died a natural death in most communities. The government needs to establish clear policy guidelines against the exploitation of the child,” he said, stressing that it should ensure that the two ministries responsible for children come together and look at the laws that protect children, particularly the Anti-Human Trafficking and Migrants Act and the Child Rights Act 2007, to develop working document for managing children’s affairs.

![A group of children with an average age of 13-years working at a construction site [Kailahun market] in the eastern Kailahun District of Sierra Leone. Photo credit, Stephen Lansana.](https://manoreporters.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/A-group-of-children-working-at-a-construction-site-Kailahun-market-in-Kailahun-750x375.jpg)