By Kemo Cham for The East African

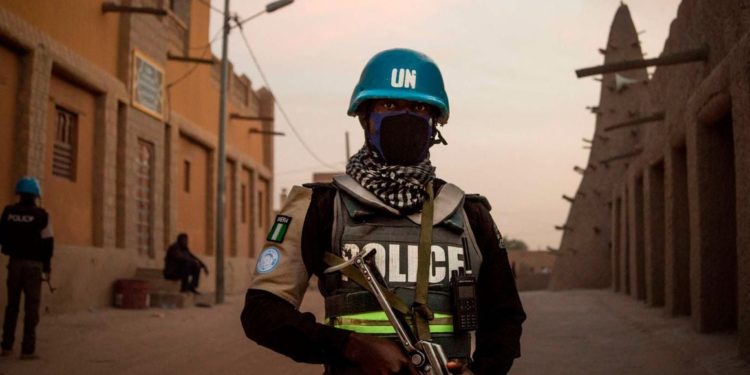

Mali’s decision to reject the continued stay of the UN peacekeeping mission in the country is eliciting concerns from regional and international powers over the implication on the security of the region.

The junta of the West African nation had announced the decision on Friday, blaming the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali, known by its French acronym, Minusma, for failing to respond to the country’s security challenges.

“The government of Mali calls for the withdrawal without delay of Minusma,” Foreign Minister, Abdoulaye Diop told a UN Security Council meeting convened to review a UN report on the security situation in the country.

Mali has been fighting an insurgency in its northern and central regions since 2012, and the military cited failure to tame the scourge as reason to overthrow a civilian government in 2021 when Col Assimi Goïta toppled President Bah N’daw’s government.

Relations between the country and Western powers have deteriorated over the years over disagreement on how to handle the conflict which has claimed thousands of civilian lives and displaced over six million, according to UN figures.

In fact, Mali has had two coups within the last three years. Mali’s ties to Russia have also complicated the relationship.

Read: Mali junta warns peace deal under threat

The West, particularly the US and France, has accused Russia of fermenting insecurity in the region through the Kremlin backed Wagner forces, a private army which reportedly entered Mali last year.

Minusma was first deployed in 2013 to help stabilise the country after a rebellion waged by the Tuareg in the northern part of the country. With support from France, the government forces at the time forced the rebels out of power in the region. But they soon regrouped and set up bases in the desert, leading to the start of the insurgency.

Since then, several armed groups thought to be linked to ISIS and Al Qaeda have entered the scene.

The UN Mission’s mandate is due to expire at the end of June. UN Secretary General António Guterres had proposed an amendment of the mission’s mandate, which the Malians objected to.

Foreign Minister Diop was quoted saying that it made no sense for the troops to continue staying in the country after 10 years without any gains to show for it.

Even among the population there has been growing anti-UN sentiments. There was a mass demonstration in late May by people calling for the withdrawal of the troops, which they said have failed them by watching helplessly as civilians are massacred.

“Minusma seems to have become part of the problem by fuelling community tensions exacerbated by extremely serious allegations which are highly detrimental to peace, reconciliation and national cohesion in Mali,” Diop said in his speech to the Security Council.

The UN described the conflict in Mali as the deadliest, after over 300 of its 15, 000 troops have been killed there.

Read: UN: Mali army, foreign forces killed 500 people

Minusma took over as the largest UN peacekeeping mission in the world from Minusca in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where they also came under attack last year from civilians who accused them of failing to protect them in one of the world’s protracted conflicts.

Concerns over Mali’s intention to cut ties with the UN mission had brewed since July last year when the junta-led administration suspended troop rotations of the mission. That followed the detention of 49 troops from neighbouring Cote d’Ivoire who were said to be linked to the UN mission.

Read: Mali jails Ivorian soldiers for 20 years

In August that same year, the junta expelled Minusma spokesman Olivier Salgado. And earlier this year in February, it declared a senior official of the mission persona non grata, given him 48 hours to leave the country.

The Security Council is expected to pass a resolution to extend Minusma’s mandate by June 30. But experts say that’s unlikely to happen as the decision requires at least nine votes in favour, with no veto from one of the five permanent members – Russia, China, the United States, United Kingdom or France.

The announcement by the Malians comes about a week after reports that Junta leader Col, Assimi Goitta spoke with Russian leader Vladimir Putin on phone.

Read: Mali junta leader discusses security, economy with Russia

The development has further left western governments unsettled.

The United States government for one couldn’t keep mute about it.

The States Department expressed regrets over Mali’s decision in a statement on Tuesday.

“We are concerned about the effects this decision will have on the security and humanitarian crises impacting the Malian people,” it said, noting that the US “will continue to work with our partners in West Africa to help them tackle the urgent security and governance challenges they face.”

The US also reminded the Malian transition government to continue to adhere to all its commitments, including the transition to a democratically elected, civilian-led government.

Malians voted on Sunday in a referendum proposing constitutional amendments ahead of transition to democratic rule, expected in March 2024.